The Mystery of the Massive Neanderthal Nose Solved by Ancient Skull

For decades, the prominent, large nose of the Neanderthal has been one of the most distinctive and puzzling features of our closest extinct human relatives. Scientists traditionally believed this massive nasal structure was a crucial evolutionary adaptation, essential for surviving the harsh, frigid climates of Ice Age Europe by warming and humidifying the extremely cold air.

However, a remarkable discovery—a 130,000-year-old Neanderthal skull sealed deep within a remote cave in southern Italy—has provided the critical evidence needed to challenge this long-held hypothesis. The detailed analysis of this ancient specimen, combined with cutting-edge technology, suggests that the primary function of the Neanderthal nose was not superior climate control, but rather something far more fundamental: high-volume respiration to fuel an enormous, energy-intensive body.

This finding fundamentally shifts our understanding of Neanderthal craniofacial morphology and their physiological demands, moving the focus from passive environmental adaptation to active metabolic requirements.

Deconstructing the Cold Adaptation Hypothesis

The traditional view in paleoanthropology centered on the principle of thermoregulation. The hypothesis stated that the large, broad nasal cavity of the Neanderthal was an evolutionary answer to the glacial conditions they inhabited. The idea was that the expansive internal structure, including the complex network of nasal turbinates (conchae), allowed for maximum surface area to warm and moisten the frigid, dry air before it reached the lungs. This was seen as a vital survival mechanism.

The Role of Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD)

To test this hypothesis against the physical evidence provided by the ancient Italian skull, researchers employed advanced engineering techniques, specifically Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD). This method, typically used in aerospace or automotive design, allows scientists to create highly detailed 3D models of the Neanderthal nasal passage and simulate how air flows through it under different environmental conditions.

By comparing the CFD models of the Neanderthal skull with models derived from modern humans (Homo sapiens) and earlier hominids like Homo heidelbergensis, the research team could quantify the efficiency of each structure in three key areas:

- Air Warming: How effectively the air temperature was raised.

- Humidification: How much moisture was added to the inhaled air.

- Airflow Resistance: The ease or difficulty of moving large volumes of air.

The results were surprising. While the Neanderthal nasal passages were undeniably large, the CFD analysis demonstrated that they were not significantly superior to modern human noses in warming and humidifying cold air.

“The Neanderthal nose was certainly large, but its internal architecture did not show the specialized efficiency for thermoregulation that the cold adaptation theory required,” noted one of the lead researchers. “The primary difference lay in its capacity to move air rapidly.”

The High-Octane Metabolism Theory

If the large nose wasn’t primarily for climate control, what was its true purpose? The new evidence points toward a physiological necessity driven by the Neanderthal lifestyle: high metabolism and extreme energy expenditure.

Neanderthals were robustly built, highly muscular hunters who lived demanding lives in challenging environments. This physical profile required a significantly higher caloric intake than modern humans—estimates suggest they needed up to 4,000 calories per day just to maintain their body temperature and activity levels.

This high energy demand translates directly into a need for massive oxygen intake. The large nasal and sinus cavities, according to the new analysis, were perfectly optimized for:

- Increased Air Volume: Allowing Neanderthals to inhale and exhale much greater volumes of air per breath compared to modern humans.

- Reduced Resistance: The structure minimized resistance, enabling rapid, deep breathing necessary during strenuous activity, such as chasing large game or hauling carcasses.

In essence, the Neanderthal nose was less like a sophisticated radiator designed for cold air, and more like a high-performance air intake manifold designed to maximize oxygen delivery to a metabolically demanding body.

Broader Implications for Human Evolution

This discovery has profound implications for how we view the evolutionary divergence between Neanderthals and Homo sapiens.

Challenging the Climate Determinism Narrative

For years, climate has been the dominant explanation for many physical differences between hominid species. This new finding suggests that while climate was a factor, metabolic rate and dietary needs may have played a more critical role in shaping craniofacial features than previously thought. The large Neanderthal face may have evolved to accommodate the powerful muscles and large teeth necessary for processing their high-protein, high-calorie diet, with the large nose being a secondary, necessary feature to support the resulting high oxygen demand.

The Role of Genetic Drift

Another possibility that gains traction is that the unique nasal morphology was simply the result of genetic drift within isolated populations, rather than a direct, selective adaptation to climate. While the structure proved efficient for high-volume breathing, it may not have been the only way to achieve that result, suggesting a more complex interplay of factors beyond pure environmental pressure.

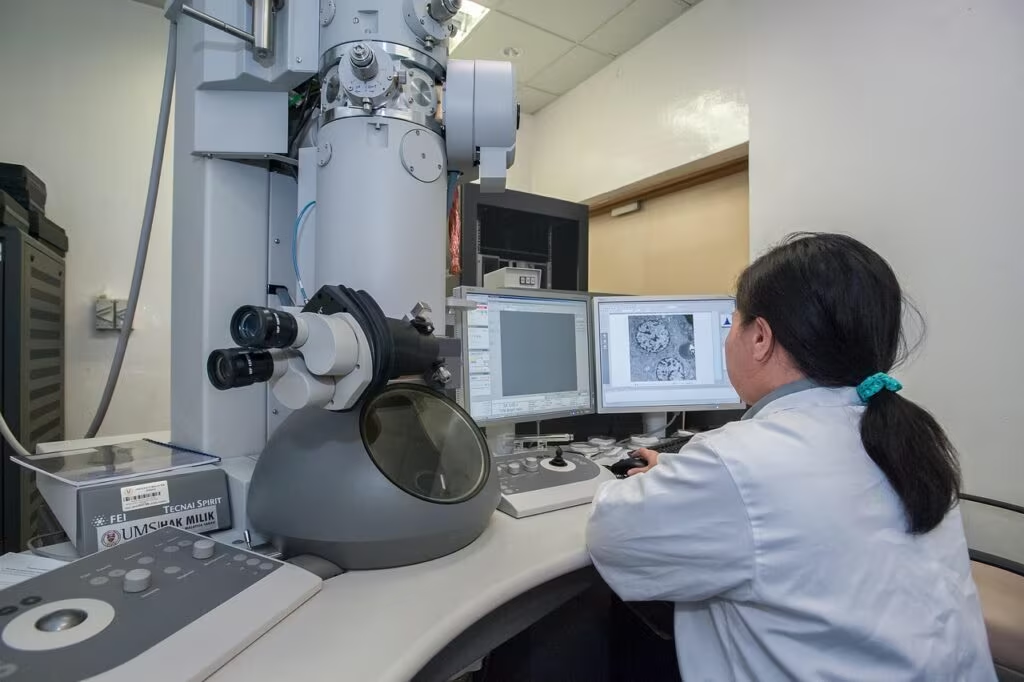

The Saccopastore Precedent

While the specific Italian skull analyzed (often linked to the Saccopastore specimens or similar finds in the region) is crucial, it reinforces a growing trend in paleoanthropology: the use of non-invasive, high-tech methods to extract maximum information from fragile fossil records. Techniques like micro-CT scanning and CFD modeling are providing unprecedented detail about the soft tissues and internal structures that are otherwise lost to time.

Key Takeaways

This analysis of the 130,000-year-old Neanderthal skull fundamentally redefines the purpose of their most famous feature:

- Challenged Hypothesis: The large Neanderthal nose was not significantly better than the modern human nose at warming and humidifying cold Ice Age air.

- New Function: The nasal structure was optimized for high-volume airflow to support an extremely high metabolic rate and strenuous, active lifestyle.

- Metabolic Driver: The need for massive oxygen intake, driven by a high-calorie diet and muscular build, was likely the primary evolutionary pressure shaping the Neanderthal face.

- Methodology: The breakthrough was made possible by applying Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) modeling to 3D scans of the fossil.

Conclusion

The discovery sealed in the Italian cave has provided a powerful corrective to decades of assumptions about Neanderthal adaptation. Rather than viewing them solely through the lens of climate survival, the evidence compels us to see Neanderthals as creatures of immense physical power, whose unique features were engineered to sustain a high-octane existence. Their large noses were not just cold-weather gear; they were the essential respiratory machinery for a highly active, metabolically demanding hunter-gatherer life in the Pleistocene era.

Originally published: November 22, 2025

Editorial note: Our team reviewed and enhanced this coverage with AI-assisted tools and human editing to add helpful context while preserving verified facts and quotations from the original source.

We encourage you to consult the publisher above for the complete report and to reach out if you spot inaccuracies or compliance concerns.